The Armenian Genocide in the American Humanitarian Imagination

Book Review: ‘Bread from Stones: The Middle East and the Making of Modern Humanitarianism’

The Armenian Weekly Magazine

April 2016

Bread from Stones: The Middle East and the Making of Modern Humanitarianism

By Keith David Watenpaugh

Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015

Paperback, 272 pages

ISBN: 9780520279322

$34.95

Among the wealth of recently published Armenian Genocide commemorative books is Keith Watenpaugh’s tour de force Bread from Stones: The Middle East and the Making of Modern Humanitarianism. With evidence gathered from a half-dozen archives, Watenpaugh situates the Armenian Genocide seamlessly within the larger history of modern humanitarianism. By telling these stories together, Watenpaugh has effectively written the Armenian Genocide back into the American humanitarian imagination, a place it once held before it was conveniently forgotten.

Bread from Stones offers an in-depth look at international humanitarian efforts on the eve of World War I, a period when, Watenpaugh argues, missionary-based humanitarian relief transitioned to a modern secular humanitarian approach. He supports this argument with the writings of philanthropists from America and Europe, among them American physician Stanley E. Kerr who stayed behind in Marash to document the atrocities committed by Turkish forces as they overran French forces in 1920 and massacred Armenians, many of whom were genocide victims who had returned at war’s end. Kerr put his own life at risk in order to document the atrocities, and it is the special care to detailed documentary evidence gathering that sets modern humanitarianism apart from earlier philanthropic models. Production of “humanitarian knowledge” included collecting eyewitness documentary evidence and photography, and the gradual secularization in tone in the writings of humanitarian workers. This shift to document humanitarian crises can also be found during the Hamidian Massacres (1894-96) in the writings of American Red Cross founder Clara Barton, German Protestant missionary Johannes Lepsius, and Ottoman Armenian Zabel Yesayan’s documentation of the massacres in Adana (1909).

The personal writings of relief workers feature prominently in Watenpaugh’s history writing and breathe life into this historic moment for humanitarianism. Noteworthy is the inclusion of writings from women relief workers, American physician Dr. Mabel Evelyn Elliot (1881-1944) of Near East Relief (NER) and Zabel Yesayan (1878-1943) of the American Red Cross. The story of the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, which later evolved into Near East Relief, is told in a way that includes Armenian philanthropic organizations and the Armenian Apostolic Church within broader international relief efforts. The influence of the memoirs of Armenian orphans who were cared for by NER—Karnig Panian, Asdghig Avakian, and Antranik Zaroukian—helped shape the outlook on the Armenian Genocide as well as note the success of the program on its graduates. So, while Near East Relief was American, Watenpaugh shows how several international players merged to publicize the Armenian cause in an effort to recover national rights, which was emphasized above individual rights.

Watenpaugh documents the way that humanitarian workers and international human rights advocates understood the unfolding crisis in the Ottoman Empire during World War I through the lens of what he calls a humanitarian imagination, which marked certain individuals as objects of organized compassion. This compassion, however, did not come without some benefit since it was informed by what Watenpaugh calls American humanitarian exceptionalism, which held relief efforts to be “a means to an end of the social, political, and moral reordering of the region.” The political calculation made by international relief agencies can be observed in responses to crises resulting from the famine caused by a combination of locust infestation and the Allied blockade against the Ottoman Empire. The war prompted the Ottoman government to shift the flow of supplies to the front, leaving many of the empire’s poor without food. Discussion of the famine in Beirut, the floods in Baghdad, and food shortages in Jerusalem sets up a context for humanitarianism in the Middle East at the beginning of the war. Organizations like the American Red Cross were already on the ground in Beirut distributing food; yet, humanitarianism was more complex in areas like Palestine, where Zionist relief organizations framed deservingness along sectarian lines. This track is followed up in the coverage of the Armenian Genocide when humanitarian workers understood the genocide in largely civilizational terms and offered targeted assistance to groups considered protégés of aspirational empires.

The richness of documentation offered by Watenpaugh pulls the reader into how international bodies tried to make sense of the senseless act that was the Armenian Genocide. Accounts of trafficking of women and children resonated with 19th-century slavery abolition and fed into civilizational narratives. Rescuing Armenians was an extension of the white man’s burden and civilizing mission, both situated within the emerging concept of humanitarian intervention. In this way, as products of their time, many of these emerging humanitarian agencies “embraced modes of colonialism—most importantly a civilizing mission—without possessing a colony, and consequently without the attendant brutality.”

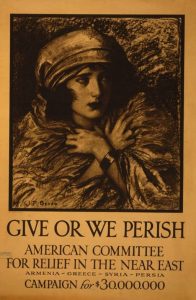

Deservingness was formulated through unstrangering the object of humanitarian assistance. This was achieved through a number of rhetorical devices, visual and linguistic, to effectively portray Armenians as civilizationally similar to Americans, thereby unstrangered and legible for humanitarian relief. “Instead of making new Near Easterners, NER had helped make new Americans in the Middle East, or at least Armenians who were both modern but still ‘out of place’ in the societies where they found refuge.” The issue of deservingness raises a number of interesting questions for the treatment of subsequent refugee flows throughout the 20th century to the present.

While we are currently living through the largest refugee crisis since World War II, Watenpaugh gives us food for thought as we think historically and critically about the problem for humanity.

A problem for humanity because it was a problem of humanity, the Armenian Genocide was a staging point for the mobilization of contemporary human rights thinking. Reading Watenpaugh’s work on the fifth anniversary of the Syrian Uprising-turned-proxy war is a potent reminder of how regressive the American—and to a greater degree the world’s—approach to refugees is compared to a hundred years ago. The Armenian Genocide mobilized humanitarian relief to the point where Near East Relief alone raised $110 million dollars by 1921 and fed 300,000 people daily; such massive humanitarian assistance lies in stark contrast to the decaying ethical standards surrounding the problem of humanity today. By the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), the world had abandoned its commitment to national recovery previously offered to Armenian refugees. Importantly, Watenpaugh suggests this may have modeled the approach to future refugee crises, including the Palestinian refugee crisis of 1948. As an international community, we are no longer troubled by statelessness. While we are currently living through the largest refugee crisis since World War II, Watenpaugh gives us food for thought as we think historically and critically about the problem for humanity. The turn toward popular vilification and criminalization of refugees over the last year provides us with examples of strangering that unravels the humanitarian imagination Watenpaugh so carefully constructs in his work. While we are unlikely to see any end to this suffering, we can consider how Watenpaugh’s broader question of deservingness bears on contemporary realities and ask, What it is that makes some communities less deserving than others of humanitarian assistance?

Source: Armenian Weekly Mid-West