China as Refuge for Armenian Genocide Survivors

From the Armenian Weekly 2016 Magazine

Dedicated to the 101st Anniversary of the Armenian Genocide

China as Refuge for Armenian Genocide Survivors [1]

In a letter to his brother Krikor,[2] who had arrived in Boston in 1914, Rev. Asadoor Z. Yeghoyan wrote from Kharpert, “Krikor you traveled all around the world, now you know by experience that the world is round, take care so you will not fall off it.”[3] The reverend’s words were not true, yet they were prophetic. At that point, Krikor had not traveled around the world—he had left the Ottoman Empire and crossed the Atlantic for the United States. However, Krikor returned to his home town shortly thereafter and was caught in the maelstrom of World War I. He survived the Armenian Genocide with the help of Kurds from Dersim and eventually arrived in the Caucasus. Yet conflict in the region kept pushing him eastward, until he reached China. In 1919, he finally arrived in the U.S. via Japan, with help from Diana Apkar, the honorary consul in Japan of the first Republic of Armenia. At that point, he had indeed traveled around the world. In this article, I present a brief history of the several thousand Armenians who, like Krikor, escaped the genocide and found safe haven in China.

Armenians in China (1880s-1950s)

Armenian boy, Setrak Antonyan, in Tientsin, China, 1936 (Photo: Meltickian Collection, SCU Fresno Armenian Studies Program Library)

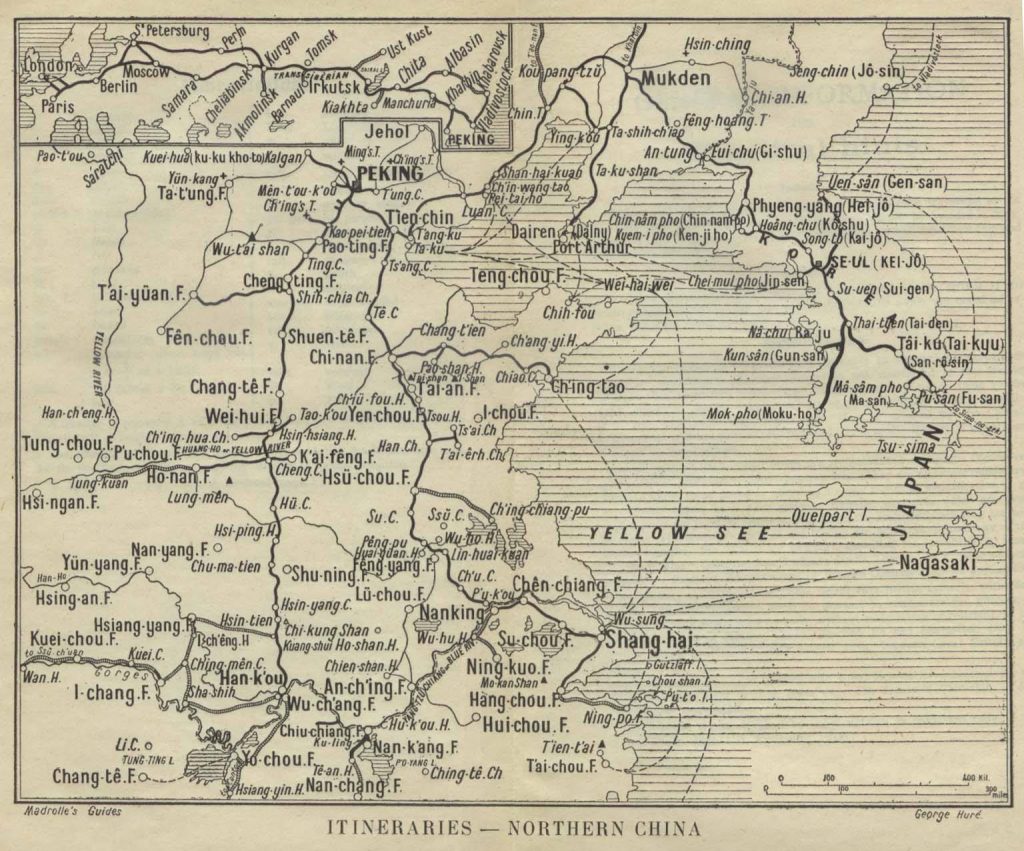

Hundreds of Armenians journeyed eastward to China in the late 19th century in search of opportunity, anchoring themselves in major cities, as well as in Harbin, a town that rose to prominence with the construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway.

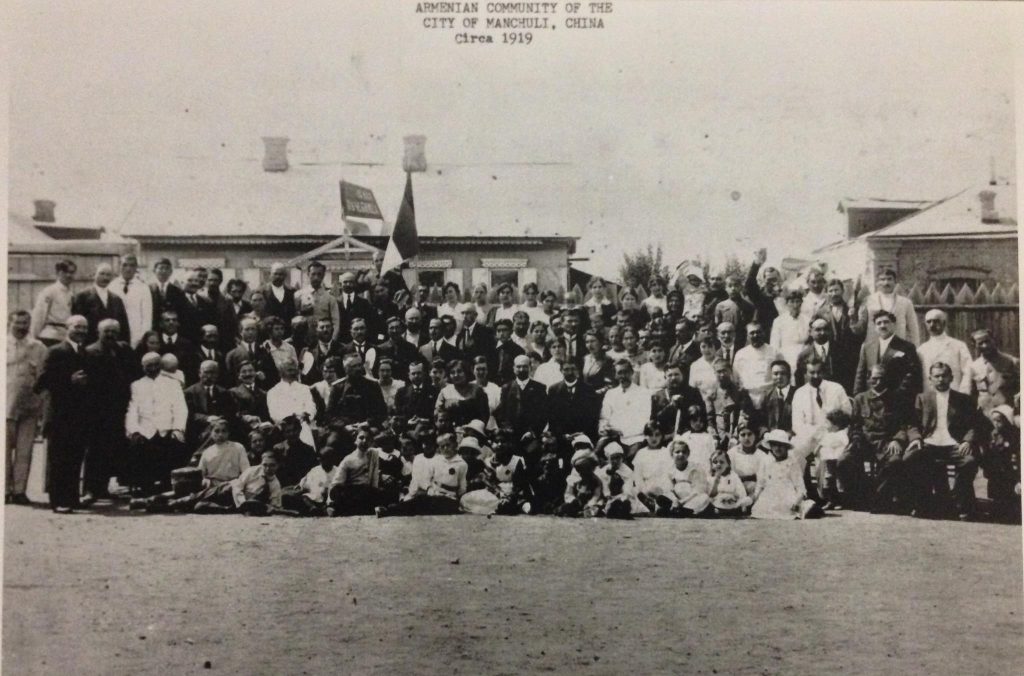

Initially, Armenian railroad workers and merchants formed the core of the community in Harbin. Their numbers were small—no more than a few dozen. A larger number of Armenians lived in Manzhouli (Manchuli), which had risen to prominence in the early 20th century also thanks to railway projects. A group photograph of the Armenian community in Manzhouli (circa 1919) depicting around 150 men, women, and children, complete with the Armenian tricolor, stands testament to the size of the Armenian community in the city.[4]

A few thousand Armenians, including Yeghoyan, arrived in the region escaping genocide in Ottoman Turkey and turmoil in the Caucasus. Often, those who followed this path hoped to get to the United States. American missionary Ernest Yarrow encountered some 200 Armenian refugees in Vladivostok in late 1918, most of whom “have friends in America and are hoping in some way or other to get there.”[5] Yet most stayed in East Asia for years, even decades, helping build communities that thrived, despite conflicts, war, and foreign occupation.

Many of these Armenians coupled their personal success with a dedication to community life, helping develop small but vibrant communities. Despite conflicts, war, and foreign occupation that beset the history of China in the first half of the 20th century, they built a church (Harbin), community centers (Harbin and Shanghai), and established relief organizations, choirs, language schools, and women’s groups. In the years following the Chinese revolution, Armenians fled the country (like most Christians in China) mainly in two directions: Soviet Armenia and the Americas.[6]

Garabed Meltickian was a survivor of the genocide who joined the stream of Armenian refugees traversing the Caucasus and Siberia all the way to China. Originally from Maden, Diyarbakir, Meltickian was conscripted into the Ottoman military in 1914 and dispatched to Erzincan. In 1915, he was among 120 Armenian soldiers who were handcuffed and taken away to be killed. He miraculously survived the carnage, was given shelter by Kurds, saved by advancing Russian troops, fought with Armenian forces in Kars, and after their withdrawal from the city, went to Tiflis, from there to Siberia, and finally settled in Manchuria.[7] Meltickian became a successful merchant in the city, and played an active role in the Armenian community’s life. He helped form a youth group and started a small Armenian library, arranging for the shipment of books from Hairenik publishing house in Boston, Mass.[8]

Soon, the first generation of Armenians born in the city started successful businesses in China. A son of survivors, Yervand Markarian was born in Harbin, where his father had settled after the war. The family moved to Tientsin,[9] China, in 1925.[10] Years later, reflecting upon his life’s trajectory, Markarian wrote:

I was a man born outside my ethnic fatherland which by the time of my birth had ceased to exist… As incongruous as it may seem, I was born in China, without having a drop of Chinese blood, where I later volunteered to serve in the French army but was not French, and ended up in the French Foreign Legion in Indochina (Vietnam), under rather strange circumstances. As a family man, I owned and managed restaurants in China, Brazil, and California—all of them Russian/Armenian and all of them called Kavkaz.[11]

Newspapers in China and the Genocide

Many in China were not oblivious to the fate of Ottoman Armenians as hundreds of survivors arrived in Harbin and other cities. Russian, English, Chinese, and Japanese language newspapers reported on the fate of the Ottoman Armenians. The North China Herald (published in Shanghai beginning in 1850), for example, ran dozens of reports on the Hamidian massacres, the Adana massacres, the Armenian Genocide, relief efforts to assist Armenian deportees and refugees in the Caucasus and in Syria, peace treaties and negotiation processes involving Armenian representatives, and the Armenian communities in Harbin and Shanghai as they established a church and a community center. A report titled “Massacres in Armenia. Horrible Atrocities” (4 December 1915), provided details furnished by Viscount Bryce about massacres in Bitlis and Mush and drownings in River Tigris. Another article, “Awful Massacres in Armenia. Wholesale Drowning at Trebizond” (16 October 1915) noted how in the House of Lords, Earl Cromer said Germany’s “moral responsibility [in Armenian massacres] was unquestionable.” The author called for “utmost publicity” in India and Egypt expressing belief that educated Muslims there would be equally outraged by the atrocities. The author went on to argue that the only way to rescue the survivors would be “an expression of opinion from the World, especially from neutrals.”

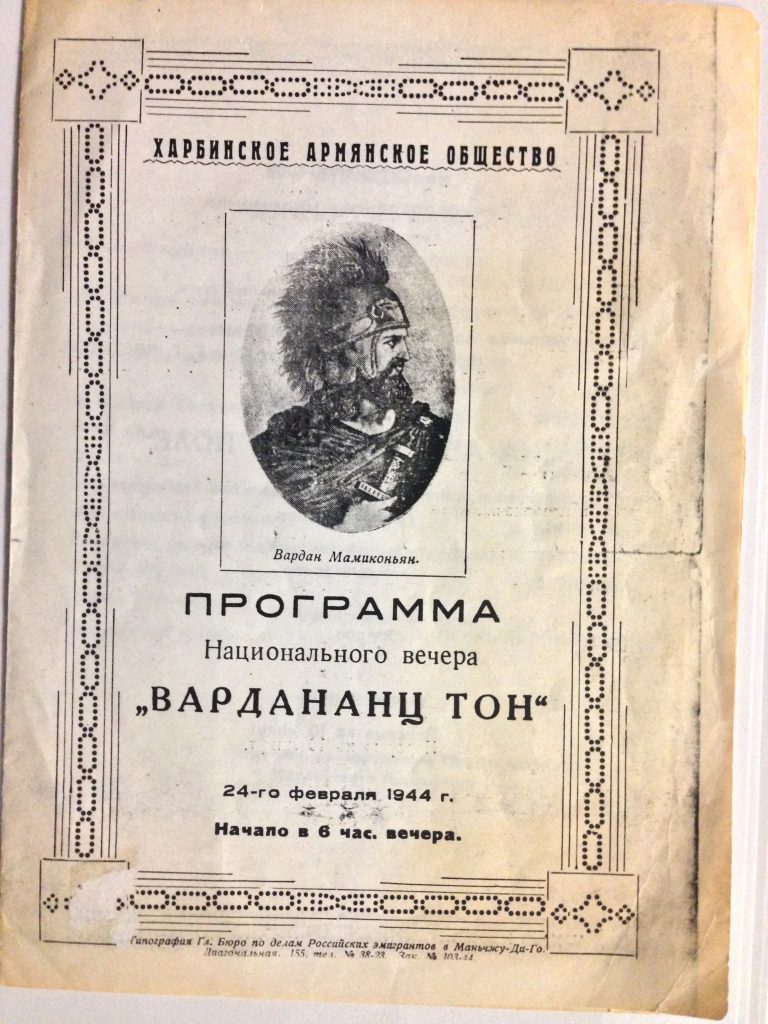

Program booklet cover of Vartanants Day event in Harbin (Feb. 24, 1944) (Photo: Meltickian Collection)

Interactions with Missionaries

The role of missionaries in providing relief and assistance to Armenians during and in the aftermath of the genocide is well-documented, with focus on humanitarian work in the Ottoman Empire and the Caucasus.[12] Yet missionaries assisted Armenians, including deportees who had escaped the genocide, also in faraway cities like Vladivostok and Harbin. One such missionary was Rev. Ernest A. Yarrow, who spent almost a year in Siberia and Manchuria beginning in late 1918, following a decade of service in Van (September 1904-October 1915) and the Caucasus (1916-1919), before another five years in the Caucasus with Near East Relief (1920-1925).

Working for the Red Cross in Vladivostok, Yarrow helped house refugees “among whom were about 200 Armenians who had come from the Caucasus, some of whom I knew personally.”[13] Now in East Asia, Yarrow once again embarked upon helping Armenians from the Ottoman Empire and the Caucasus. “Among those whom I knew were Aghavnee and Marina, who were teachers in our school [in Van] and whom I put in charge of the stores until they got permission to leave. I got them good outfits of clothing and left them quite happy,” he wrote.[14]

Yarrow employed several Armenians, and secured jobs for many others. Armenian refugees in Siberia and Manchuria remembered Yarrow fondly for his efforts. In his memoir, Krikor Yeghoyan wrote:

[W]e visited Vladivostok [from Harbin]…. The first wagon rolling in was the one with the Armenians. At this instant we noticed one gentleman and two nurses. The nurses came over; they asked us, “Are you Armenians?” in Armenian. We answered, “Yes.” Right away they asked us if there were any tradesmen amongst us. I said I was a carpenter. The man said, “Good.” He left the nurses here and brought me to a town to meet the General. On our way, I asked him how come he knew such good Armenian. He said he was a missionary in Van. He learned it there and his name was Yarrow. I became very interested in the man. I asked him this time if he ever went to Harpoot. “Yes, but only for conventions.” In that case I suppose you must know Rev. Yeghoyan [Krikor’s brother]. “Oh, yes,” he said, he was a powerful minister. I continued saying, I was his brother, that I was in America one time, and doing carpentering there. “Do you speak English?” “Yes, a little,” I said. “Oh, you are just the man we are looking for!” At last I met the General; Yarrow introduced me to him giving all the details of my life and adding that I had been in U.S.A. After this formal conversation, I was appointed as supervisor over all the refugees, and master carpenter with a salary of 400 rubles, also board and lodging.[15]

Not all refugees Yarrow helped in Vladivostok anchored themselves in Siberia and China. Arriving in Egypt in March 1919, Yarrow met with several of the Armenians he had helped in Vladivostok months earlier. They were at the Armenian refugee camp in Port Said that was comprised of several thousand Armenians rescued by a French battleship from Musa Dagh, and a few thousand Armenians from elsewhere. “You remember my writing from Siberia that I had housed and organized the support of about 200 Armenians in Vladivostok?” Yarrow asked in a letter to his friend. “I was amazed to find that 35 of these had reached Port Said and were in the camp. They had been sent by boat by the Red Cross to make their way back to Armenia!”[16]

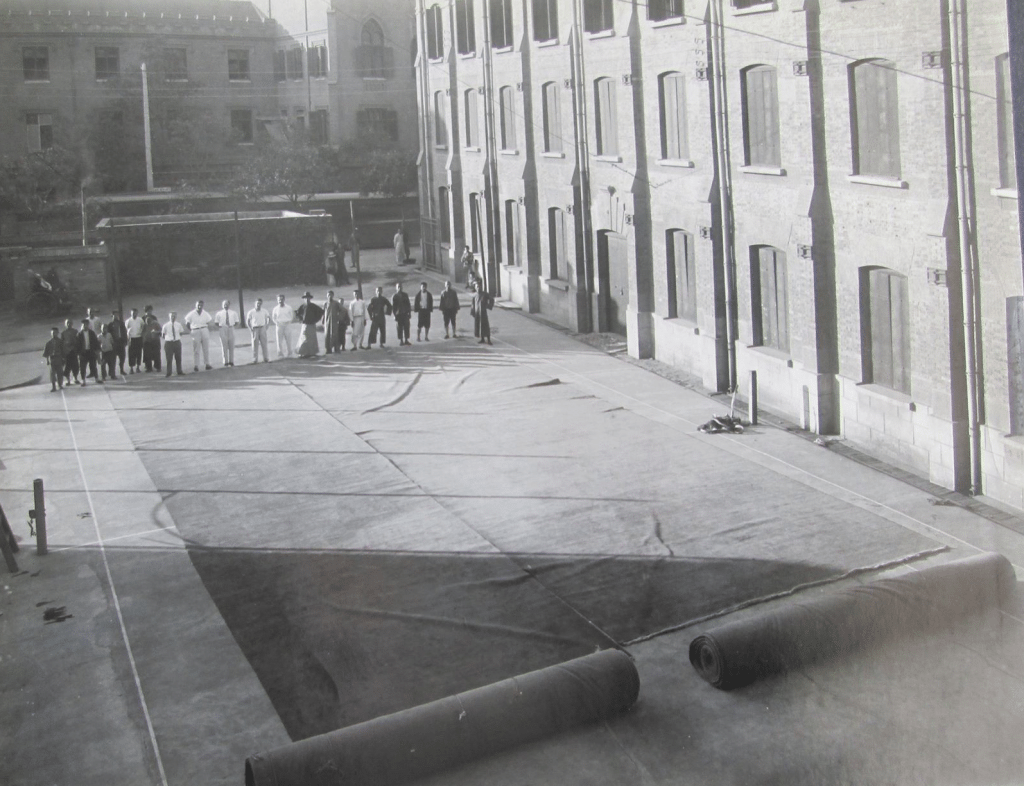

The A & M Karagheusian rug factory was one of the hugely successful Armenian-owned businesses, which employed hundreds in China and the U.S. (Photo: Elise Kazanjian family archive)

Conclusion

For several decades, hundreds of genocide survivors called China home, helping build communities that celebrated heritage and culture across the globe from the Armenian homeland. The Chinese revolution displaced these Armenians once again, scattering them across the globe—to Soviet Armenia, North America, and Australia. Thousands of documents, photographs, artifacts, and mementos from these communities are scattered in archives and family collections across the world. This article, and the more extensive study it is based on, is an effort to shed light on this integral yet neglected part of Armenian Genocide and Diaspora studies.

Notes

[1] This article is part of a much more detailed research report on the history of the Armenian communities in China in the 19th and 20th centuries, which will be published in an edited volume. I would like to thank the Gulbenkian Foundation for granting me a research fellowship that made this work possible. I would like to express my gratitude to Razmik Panossian, George Aghjayan, Ara Sanjian, Mimi Malayan, Edward G. Sergoyan, Matthew Karanian, Marc Mamigonian, Liz Chater, Elise Kazanjian, Barlow Der Mugrdechian, Henri Arslanian, and Xi Yang, for pointing me to—or providing me with—documents and photographs that proved crucial for my research. I thank the staff of Shanghai Library, Bibliotheca Zi-Ka-Wei (The Xujiahui Library), Guangzhou Library, The Armenian Studies Program at the University of Fresno, Harvard College Library (special collections and government documents), The National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (NAASR), the Armenian Studies Program at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, the Hairenik Association, the National Library of Armenia, and the libraries at Haigazian University for their help during my research.

[2] Krikor Z. Yeghoyan’s unpublished memoir, The Story of My Life, was written in 1952. Victoria Dadekian prepared a condensed English translation in 1970, which I cite in this report. I would like to thank Mimi Malayan for bringing the memoir to my attention. It is available at: http://issuu.com/dianaapcar.org/docs/memoir__the_story_of_my_life__by_krikor_z._yeghoya/1.

[3] Yeghoyan, The Story of My Life, 4.

[4] “Armenian Community in the City of Manchuli, China circa 1919,” in Meltickian Collection, Armenians in China Album No. 2, 1916-1953.

[5] Letter from Yarrow to Rev. Dr. Earle H. Ballou (20 November 1918). ABC 16.9.7, vol. 25d, item 260 (Papers of the ABCFM, reel 717). Dr. Ballou worked for ABCFM in China from 1917 until WWII.

[6] A few families, for example, settled in Australia.

[7] H. Bsag (Hamazasb Bsagian), “Garabed Mldigian,” Asbarez Daily, 12 April 1963.

[8] Ibid. Meltickian passed away in 1937. His wife and daughter eventually settled in Fresno, Calif. The Meltickian Collection referenced in this article is donated to the University of Fresno’s Armenian Studies Program by his daughter, Virginia Meltickian.

[9] Several dozen Armenians called Tientsin home in the 1920s and 1930s. According to an Etchmiadzin document providing figures for 1933-1934, there were 70 Armenians living in the city. See National archives of Armenia. Fund of the higher spiritual council of St. Echmiadzin. № 4732 as cited in I.D. Minasyan, “Socio-Economic Activity of Armenians in China,” in B.H. Yerznkyan, ed., Theory and Practice of Institutional Reforms in Russia / Collection of scientific works (Moscow, CEMI Russian Academy of Sciences), Issue 22 (2011), 63.

[10] Yervand Markarian, Kavkaz: A Biography of Yervand Markarian (United States: 1996), 7.

[11] Ibid., 2.

[12] See, for example, Suzanne E. Moranian, “The Armenian Genocide and American Missionary Relief Efforts,” in Jay Winter, ed., America and the Armenian Genocide of 1915 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003); Peter Balakian, The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America’s Response (New York: Harper Collins, 2003); and Hans-Lukas Kieser, A Quest for Belonging: Anatolia beyond Empire and Nation (19th–21st centuries), (Istanbul: Isis, 2007).

[13] Letter from Yarrow to Rev. Dr. Earle H. Ballou (20 November 1918). ABC 16.9.7, vol. 25d, item 260 (Papers of the ABCFM, reel 717). Dr. Ballou worked for ABCFM in China from 1917 until WWII.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Krikor Z. Yeghoyan, The Story of My Life, 28.

[16] Letter from Yarrow to Rev. Dr. Earle H. Ballou (14 March 1919). ABC 16.9.7, vol. 25d, item 264 (Papers of the ABCFM, reel 717).

Source: Armenian Weekly Mid-West