Ekmanian: Global Resistance Continues 101 Years after Genocide

Ekmanian’s Opening Remarks at Genocide Commemoration Program in Berlin

For the second year in a row, the Maxim Gorki Theater in Berlin organized a program of events dedicated to the anniversary of the Armenian Genocide anniversary.

This year’s program, which took place April 22-24, included the screening of Syrian-Armenian Director Avo Kaprealian’s “Houses Without Doors” which premiered at the Berlinale 2016, as well as music concerts by Eileen Khatchadourian, Muammer Ketencioglu, and Stepan Gantralyan, and lectures. Some performances from last year’s program, such as “Auction of Souls,” a staged-reading by Canadian-Armenian actress and director Arsinée Khanjian, “Musadagh” documentary-theater by Hans-Werner Kroesinger, and the “Auroras” video installation by Cannes winning director Atom Egoyan, were also featured this year.

Silvina Der Meguerditchian was also present at this year’s program with a new installation called “SURvive,” a tribute to Diyarbakir’s Sur district, which, after having suffered the destruction of its Armenian population and heritage a hundred years ago, is experiencing a new wave of violence today. The events kicked off on April 22 at the Maxim Gorki Theater, with a keynote opening speech delivered by New York based journalist and lawyer Harout Ekmanian. The following is the text of his speech.

***

‘This is a knife, an axe, which committed many atrocities. Breaking the knife or the axe cannot heal those atrocities and persecutions… The blood of the innocent is still on it… There is no limit to the amount of houses it destroyed and burned… We must not only reject it, but also demand the punishment of those who destroyed the country using such laws with criminal intent.’

Ladies and Gentlemen,

This is a quote from the surviving Armenian member of the Ottoman Parliament from Aleppo, Artin Boshgezenian. He uttered these words on Nov. 4, 1918, when Constantinople was under Allied occupation. He was addressing fellow parliamentarians during a session on the removal of the notorious “deportation” law of May 1915 and the law of confiscation of properties of September that same year. These were laws that were the basic pillars of the Armenian Genocide 101 years ago. They were axe that broke the back of an entire civilization that had flourished for more than three millennia in the Armenian Plateau.

Garo Paylan holds up his identification card during a speech in Parliament on Jan. 13. (Photo: Ermenihaber.am)

Last month, an Armenian member of the Turkish Parliament, Garo Paylan, gave a similarly heart-wrenching but at the same time very powerful speech in Ankara about the crimes of the Turkish state in the majority Kurdish eastern provinces. In his 20-minute address to fellow parliamentarians, he underlined the situation by saying, “We simply don’t learn from our history!”

They say that there are two histories: One of the people and another of the rulers. Over the last 100 years, the history of the rulers in Turkey has never deviated far from the invariable line of the late Ottomans, despite all its catastrophic consequences. There has always been a state mentality and approach that confronts human rights issues with destroying villages and cities, killing civilians, deporting and uprooting the survivors, plundering their properties, and confiscating their lands.

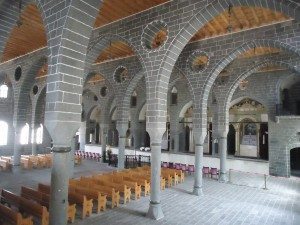

The latest casualty of this pernicious destruction in Turkey was the historic town of Sur in metropolitan Diyarbakir, (Dikranagerd or Amed), as well as Cizre, Silopi, and others. In Sur, most Armenians were annihilated in 1915 and their properties were confiscated—or AXED, in the words of Deputy Boshgezenian. A century later, this town was emptied again, this time of its Kurdish inhabitants, many of whom were killed in cold blood. Almost 85 percent of an entire city’s private properties were confiscated by the government—AXED again! The largest Armenian church in the Middle East, Saint Giragos of Diyarbakir, which barely recovered from the first assault, was subjected to another.

Ironically, with the start of the uprisings in the Arab world in 2010, many European leaders found the remedy to all of the social and political problems plaguing countries from Tunisia to Syria within this controversial Turkish model. A government that proudly holds third place—after China and Egypt—as the world’s top jailer of journalists, and that cracks down on academia and opposition media, was lauded as a model to follow for millions of Arabs who were testing freedom of expression for the first time in decades. A government that denies the existence of millions of skeletons of its Armenian, Assyrian, and Greek citizens in its closet—that government was being praised as a progressive model to look up to. It seems that not only did Turkey’s ruling politicians confuse “democracy” with “majoritarianism,” but so did Europeans and other countries that claim a deep commitment to the universal value of human rights.

Setting Turkey’s historic record straight is more critical today than it ever was because, by continuing the denial, the government of Turkey is condoning the Armenian Genocide and today continues to implement similar exclusionary and violent policies against its citizens.

Today, world leaders, one after the other, are succumbing to blackmail by the Turkish government–sometimes under the illusion that Turkey is an indispensable ally in the fight against the so-called Islamic State, and sometimes to shamelessly keep refugees literally at bay. Erdogan recently “thanked” his Western allies in his own special way: Two weeks ago, his guards roughed up reporters in front of a think-tank in the middle of Washington, D.C., giving Americans a taste of daily life in Turkey. And just days ago, he mocked Europe’s freedom of speech by pushing for the prosecution of a satirist in Germany for having criticized him.

The Armenian Genocide was commemorated on April 24 at Istanbul’s Hayderpasha train station. (Photo: Hrant Kasparyan)

One must be naïve to think that such governments and politicians are up to the challenge of facing history, recognizing past atrocities, and committing to human values. However, if the West really wants to set a good example for societies struggling for peace and democracy in this region, they need to start by rejecting the bullying by Turkey’s autocrats, and instead supporting the independent voices, the free media, the fragile civil society, and all the crushed and oppressed groups across the country. Turkey today has another minority that is not defined by ethnicity or faith; rather, it is made up of various citizens who dare to challenge the monolithic narrative of the state. I believe that this minority, along with other minorities, will play a very important role in the democratization of Turkey because, after all, only a democratic Turkey based on rule of law, separation of powers, women’s rights, minority rights, cultural and political diversity, media freedom, and freedom of speech, will be able to face its past, take responsibility for its actions, and build a future based on mutual trust and respect with all its citizens and neighbors.

Each year, the snowball becomes bigger and bigger. With each bullet that was fired in Sur, Cizre, or Silopi a few months ago, the ghosts of Turkey’s past were resurfacing. The chants of the Turkish police against the Kurds—“You are all Armenians, traitors!” —and Davutoglu’s remarks in Bingol likening today’s struggling Kurds to “Armenian gangs who cooperated with Russia 100 years ago” are clear symptoms of a poisoned mentality that is eating Turkish society and individuals from the inside. Turkey’s recognition of the Armenian Genocide, and opening up to its history and correcting past mistakes, has become as important for the future of Turkey and the entire Middle East as it is for Armenia itself.

They say that there are two histories: One of the people and another of the rulers. Unlike the rulers, I think that the people are better equipped to learn from history and to not repeat it. As much as it is hard to be positive in light of what is happening today in Turkey, Syria, the Nagorno-Karabagh Republic, and other places, being pessimistic doesn’t help either. Last year at this time, I stood here and told the audience that “a century has passed, but we’ve learned so little.” Today, however, I’ve come here with an important correction to the statement: History repeats itself; however, despite it all, we have at least mastered one art—and that is resistance. These events in Berlin, and others in Istanbul, Yerevan, and other places, are all a part of the global resistance that guarantees our collective future.

Thank you.

Source: Armenian Weekly Mid-West