The Search for a Master’s Legacy

LOWELL, Mass.—Mehmed Ali could very well be the best friend any Armenian could have.

Aside from moral support, he’s donated money to genocide observances in this mill city, taken part in commemorative marches downtown, and conducted a month-long series of programs as former director of the Mogan Cultural Center, which partially funded many a commemoration.

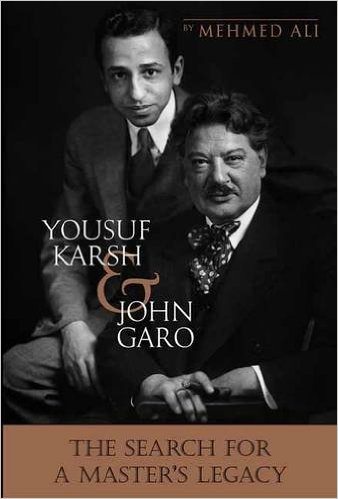

And now, he’s come forward with a book encompassing the lives of two very prominent Armenian photographers of our time: Yousuf Karsh and his one-time mentor John Garo.

The fact he’s of Turkish extraction pays little or no consequence.

“It’s been a work in progress over the past six years,” said Ali. “The more I delved into their lives, the greater understanding and respect I had for their work.”

Titled The Search for a Master’s Legacy, the book takes into account perhaps the greatest portrait photographer of his time, and the Boston mentor who taught him the ropes as a child. The chemistry each shared with their cameras and meager darkroom furnishings transcends both time and tradition.

Much of it was provided through personal interviews with Karsh’s widow Estrellita, who resides in Boston, where Karsh also made his home before passing on.

The paperback work, published by Benna Books of Mansfield, contains 192 pages with more than 100 illustrations, and sells for $24.95. Further details are on www.BennaBooks.com.

“Drawing upon some meticulous research and on Karsh’s personal correspondence, the book brings to life this intensely human journey, along with the little known story of Garo’s stellar role in the history of New England photography,” said Ali.

“This story illustrates how to persevere through life’s challenges, how to establish yourself as a leader in the art community, and how experiencing all life has to offer to create meaningful art,” he added.

In a conversation with this author, Ali offered much insight into the book as well as the two photographers. Many books have been written by and for Karsh over the past half century. But little is known about the man who made Karsh possible.

“When President Calvin Coolidge was asked to choose between the artist John Singer Sargent or the photographer John Garo to make his official presidential portrait, Coolidge chose Garo,” Ali pointed out.

“He was a nurturing and encouraging mentor. Karsh’s three years with Garo transformed his young life and influenced his original desire to portray those personalities who made a positive impact in the world,” Ali added.

When Garo died in 1939, it was Karsh who transfixed the photographic world with a number of presidential portraits and heads of state, movie stars, noted scientists, literary icons and common, everyday folks he preferred capturing.

It was to this humanistic atmosphere of Garo’s sky-lit studio that the fledgling photographer, a survivor of the 1915 genocide, was sent by his uncle George Nakash to become Garo’s apprentice.

The studio was located at 739 Boyalston St. in downtown Boston on the top floor of an apartment complex. At the turn of the 20th century, approximately 30 professional photographers lined the 1.5-mile stretch from Washington St. to Massachusetts Ave.

Karsh was certainly in his young entrepreneurial element and, no doubt, learned from other masters as well. The skylight was a perfect atmosphere with which to radiate and illuminate his subjects.

“Garo also painted watercolors, wrote poetry, and was counted among his friends in the world of theater and music,” Ali writes. “When he died in 1939, Garo was a victim of the Great Depression, ill health, and changing photographic tastes.

“When Karsh arrived here from Canada, he was devastated to discover Garo’s studio ransacked and many of his portraits missing,” Ali continued. “Thus began a 40-year odyssey by Karsh to discover his mentor’s portraits and preserve them for posterity.”

At last year’s genocide commemoration in Lowell, Ali was so adamant about justice and recognition, he carried a sign that read, “Fellow Turks. Don’t deny history.”

“I wanted to tell the naysayers that you cannot deny the fact that 1.5 million Armenians died under the Ottoman-Turkish watch,” he said. “The critical role of any government is to protect its citizens, and the Turks did not do that. We need to establish dialogue and understand one another so some resolve can be made between the two countries.”

A number of Armenians applaud Ali for his defiant exercise against the Turks and thank him for being a part of their Armenian community. What matters most to him is keeping the record straight, regardless of any consequences that may intervene.

These days, Ali works as the municipality’s city historian. He has taught classes at UMass Lowell and previously worked as a diplomat in Iraq and Afghanistan. He holds a doctorate in history from the University of Connecticut.

Ali has served as a United States Marine, postman, National Park Service ranger, and diplomat, but relishes his role as father to daughter “Lom” Evelyn best of all.

Source: Armenian Weekly Mid-West